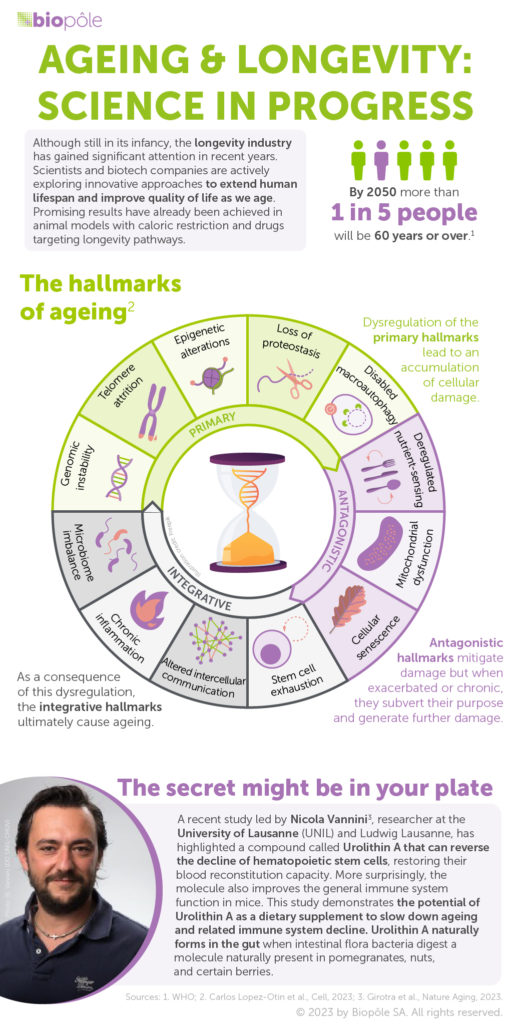

Imagine a drug that could add years on to your life expectancy. Just by taking a pill every day, you might be around for another five or ten years. You might be sceptical: don’t such drugs belong to the realm of science fiction? True, drugs to slow ageing are not yet on the market, but they may be soon. At EPITERNA, a team of 15 people work towards this very goal: finding drugs to extend the lifespans of pets and people. Co-Founder Kevin Perez tells us more.

What’s EPITERNA’s mission?

We want to help pets and people live longer and healthier lives. Our goal is not to double life expectancy, but to prolong lifespan and healthspan – the number of years someone can expect to live in good health. Preventing cancer or cardiovascular disease, for instance, could have a huge impact on your quality of life as you get older. Importantly, it would also reduce costs for our healthcare systems.

Thanks to better health standards, humans live longer than ever before. Do we need drugs to extend our lifespan even further?

Modern medicine is already trying to extend lifespans. If you have hypertension or high cholesterol, you’ll take a drug to prevent early death from these diseases – thus extending lifespan. When we treat cancer, all we’re trying to do is to give a patient more time. The difference is that since ageing is a major risk factor for many conditions, we’re trying to slow it down to prevent these diseases in the first place. Our aim is to offer a drug you can take from a certain age to prevent a plethora of diseases – as opposed to taking drugs to target a disease you already have.

How can this be done?

The concept is simple: we investigate safe, FDA-approved drugs, some of which people are already taking chronically, to test whether they could delay aging and prevent age-related diseases.

Two examples of drugs often associated with slowing down ageing are metformin and rapamycin. The first, typically prescribed to treat type 2 diabetes, works in part by restoring the body’s response to insulin. Epidemiology studies have shown that patients with diabetes taking metformin may have a longer life expectancy than non-diabetic people, but the validity of these studies is still debated. Metformin has also been shown to extend the lifespan of animals like worms and mice, although here again results are mixed.

Rapamycin, meanwhile, is a strong immunosuppressant that’s usually taken by patients who have received an organ transplant. At lower doses, rapamycin may be able to extend lifespan. This has been shown in several animal models, with some of the most notable results seen in mice.

Still, none of these drugs have been shown to extend lifespan in companion animals or humans. With this goal in mind, we investigate the possibility of repurposing drugs to prevent a wider range of diseases and therefore to extend lifespan.

How do you figure out which drugs work?

There are two sides to our work. One involves preclinical research in the lab, where we work with yeast, worms, flies, fish and mice. If we find a new or existing drug that extends their lifespan, this might later be translated to clinical research on pets and humans.

The second aspect of our work is clinical research. Right now, we’re focusing closely on dogs. We’re preparing a clinical trial for 2024 that will involve giving a large cohort of dogs a drug to test whether it can prevent multiple age-related diseases and extend lifespan.